The Nuclear Encounter Imparative

by Peter Zuspan

“In morphological progress man apparently represents only an intermediate stage between monkeys and great edifices. Forms have become more and more static, more and more dominant. The human order from the beginning is, just as easily, bound up with architectural order, which is no more than its development.” - George Bataille1

While he condemns architecture, Bataille’s words are refreshing. He believes that architecture holds significant power. His architecture is a poltergeist: a post-human agent that engineers man as the unaware means of its self-preservation and propagation. Its intelligence and productive drive operate as a passive virus, generating its own life through a static, insidious silence. Bataille’s architecture is quiet. It is the ghost in the room that is the room. It surrounds us, sitting solid and stoic.

While Bataille’s architecture is an uncanny object, it nonetheless holds its base value. It allows us to be inside it. It protects us from the elements and the exterior other. This service is comforting, albeit perhaps deceptively. The symbiosis of enclosure and construction frames a complex political history of inside and outside, a tale of binaries told by many—but what if an inside was not made for us, but for the possibility of inside itself?

“love stories are stories of form...every act of solidarity is an act of sphere formation, that is to say the creation of an interior” - Peter Sloterdijk2

Dimly lit curvature, skin on skin, writhes and presses within a cropped frame. A naked embrace is coated in what could be dust or ash. A granular albedo surfaces, the glistening coat of a precious metal, or the micro-liquefaction of freshly burned flesh, censored by black and white. The radiant ashen scar eventually dissipates, leaving a somewhat familiar texture of human skin. While unharmed, its surface remains obscure and dark.

The brief encounter of a lonely architect and a visiting actress in Alain Resnais's 1959 film Hiroshima mon Amour, coupled with its backdrop of apocalyptic aftermath, frame a strangely fertile ground, both cathartic and anticipatory. Her anguished memories and his ruined past construct a passionate yet tenuous romance, a fleeting interior of intimate enclosure.

Surrounding this intra-personal sphere sits a series of interchangeable architectural backdrops characterized by open windows, sparse rooms, raw materials, empty lots, empty bars, and the ruins of Little Boy. Resnais' architecture is vacant, quiet, and post-mortem. It is unstable, as short-lived as the interior formed by the two lovers or the suggested melting of their skin.

In Resnais’ film, Bataille’s powerful architecture is nowhere to be found. Architecture has suffered the same fate as its unknowing propagators. Even the museum seems to lose its suppressive power,3 as the camera scans through an almost vacant gallery filled with shattered architectural fragments, piles of radiated stone, and raw frames that hold the history of a city's destruction in a redundant indexing of irrepressible empathy.

The quiet, hidden power of architecture with its unyielding and haunting post-human desires is no longer possible. As Eisenhower states in a speech before the United Nations in 1953, man’s powerful edifices have become a delicate heritage, something that needs to be protected and cared for, something feeble and precious. With this decree, architecture breaks its silence and reenters the realm of contemplative culture as something to be seen, discussed, and cherished—however, now as an object in the museum, within a catalogue of dead and delicate works.

In this same speech, Eisenhower also sets into motion the international project of nuclear reactor construction.

"Since the start of the Modern Age, the human world has constantly—every century, every decade, every year and every day—had to learn to accept and integrate new truths about an outside not related to humans.” - Peter Sloterdijk4

Nuclear fission’s radiative transparency has melted the certainty of all private spheres, architectural and corporeal. It has forced a conceivable future of a permanent outside, rendering the possibility of an interior as fundamentally unstable.

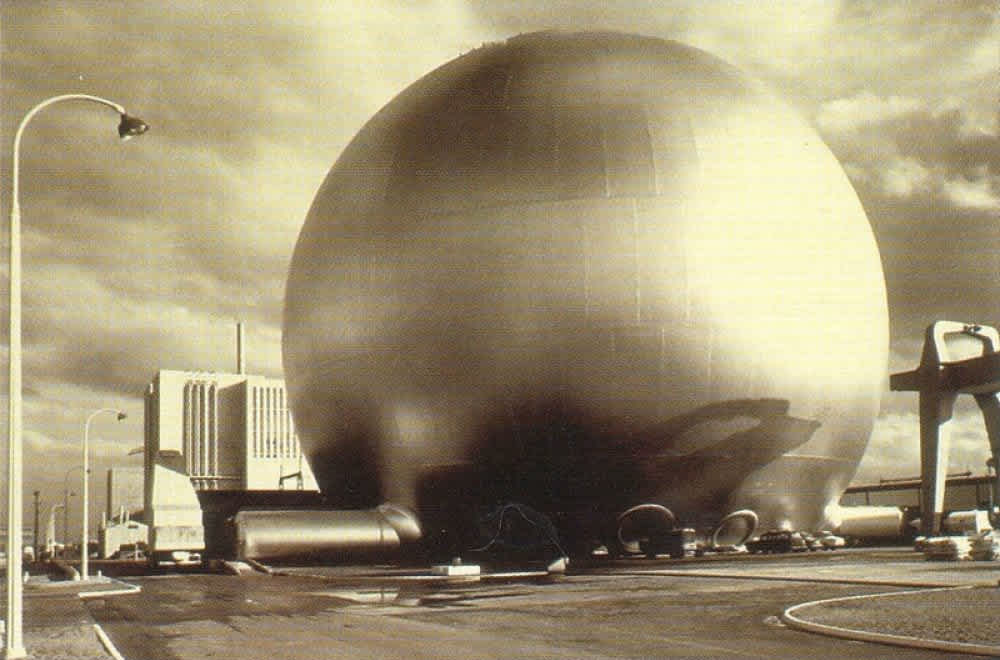

The construction of the reactor was a poetic, public, and romantic attempt to reanimate a posthumous art, combining a collective nostalgia for certainty with the certainty of scientific progress. The apotheotic reactor sought to reestablish the possibility for a stable interior through an inversion—to permanently enclose a powerfully destructive force within a sphere of monumental construction, to place the permanent outside inside.

Yet despite its spectacular edifice, on a scale far grander than anything Bataille could have imagined, the architecture of the reactor remains fundamentally weak and unstable. Its walls are fortified, but with a redundant layering of extra-architectural opacities: softly rendered utopian imagery, extra-populous sitings, a vitriolic discourse of public opinion, the ambivalence of science, the complacency of normalcy, and rigorous security protocols. The certainty of its private interior is not maintained through architectural means, but rather through methods of distraction, decoy, and digression.

The architectural encounter was at once a curse and an opportunity: a time for the victim to feel architecture’s quiet power and become infected by its viral oppression or a time for the critic to perceive architecture not as a background but as a powerful other with a will of its own.

If we are to find a meaningful way forward for a quiet, weakened art, whose fundamental nature of creating separation and inclusion can be powerful, empathetic, abusive, violent, benevolent, nostalgic or futile, we should encounter architecture in its most extreme, yet still quiet form—to pass through its build-up of layers, to look upon a sublimely precious architecture, and to gaze into its outside.

The essay was originally published in Fresh Meat Journal, Issue 10, Spring 2019.

- English translation of “Architecture” from Against Architecture: the Writings of Georges Bataille by Dennis Hollier (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1992), 53.↩

- Sloterdijk, Peter, Bubbles: Spheres 1 (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2011), 12.↩

- For more on Bataille’s opinion on the museum, see his definition “Museum,” translated by Annette Michelson, October, Vol. 36 (Spring, 1986), 24-25.↩

- Sloterdijk, 21.↩

BVA is a Certified LGBTBE.

© Bureau V Architecture 2025